A sea otter pops to the ocean surface along the Pacific coast. It is surrounded by strands of giant seaweed called kelp. The otter floats on its back. It grasps a spiny sea urchin in its little paws. The sea urchin is the otter’s favorite food.

Sea otters use stones to crack open the shells of tough-to-eat sea animals like crabs and sea urchins. (Jean-Edouard Rozey / Shutterstock)

Sea urchins have a favorite food, too. It’s the kelp. Kelp grows underwater in “forests” rooted to the rocky sea bottom. Kelp forests provide marine animals like fish safe hiding and breeding spots. Seabirds rest on the floating parts of the kelp. Tiny crabs and insects on shore use kelp, too. They feed on decayed kelp that has washed ashore.

Without the otters to devour the urchins, the urchins would devour the kelp. That would be bad news for the marine animals, birds, and crabs.

Connected and Balanced

The sea otter, urchins, kelp, fish, seabirds, crabs, water, rocks, and even the shoreline are linked together in the same ecosystem. An ecosystem is a natural community of plants, animals, and their physical environment. Everything in the natural world is part of an ecosystem.

Ecosystems can be as vast as Australia’s 1,600 mile-long Great Barrier Reef, or as small as a terrarium on your desk. Most ecosystems also connect to other ecosystems. Within every biome there are many large and small ecosystems.

Coral reefs are among Earth’s richest ecosystems. Animals called coral polyps build calcium carbonate skeletons. Over years the skeletons build into large structures that provide refuge, homes, and food for many other species. (Andrey Armyagov / Shutterstock)

Ecosystems are called “systems” for a reason. Like a smooth-running machine, all the parts are depend on other parts. Energy and material are constantly being cycled between parts. And if one thing changes, the effect can ripple through the whole ecosystem.

Ecologists—scientists who study ecosystems—know that a healthy ecosystem is also a balanced ecosystem. Like the otter, the urchins, and the kelp, each organism plays a role in keeping that balance.

Meet The Producers

Ecosystems feature a complex network of munching, crunching, growing, dying, and rotting called food webs. Food webs are the way energy moves within ecosystems. Food webs start with organisms called producers. They are called producers because they can use sunlight to produce their own food. Plants, algae, and plankton are all producers. Producers convert energy into forms that can be used by other organisms.

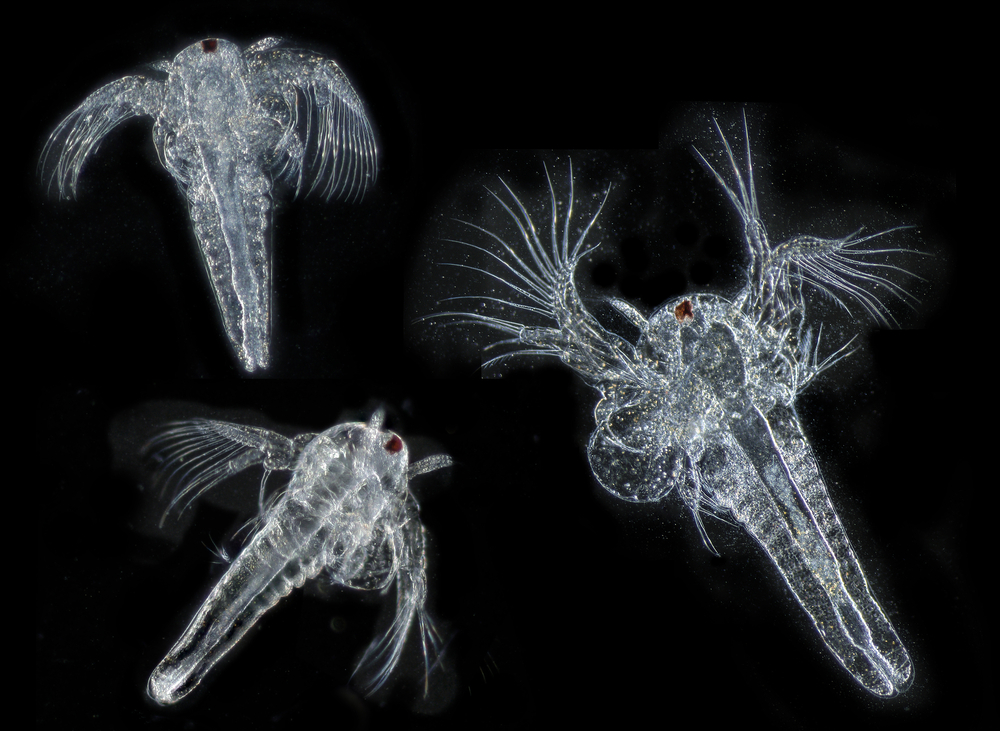

Microscopic organisms called phytoplankton form the basis for food webs in the ocean. Phytoplankton also produce oxygen, which cycles into the atmosphere. (Kuttelvaserova Stuchelova / Shutterstock)

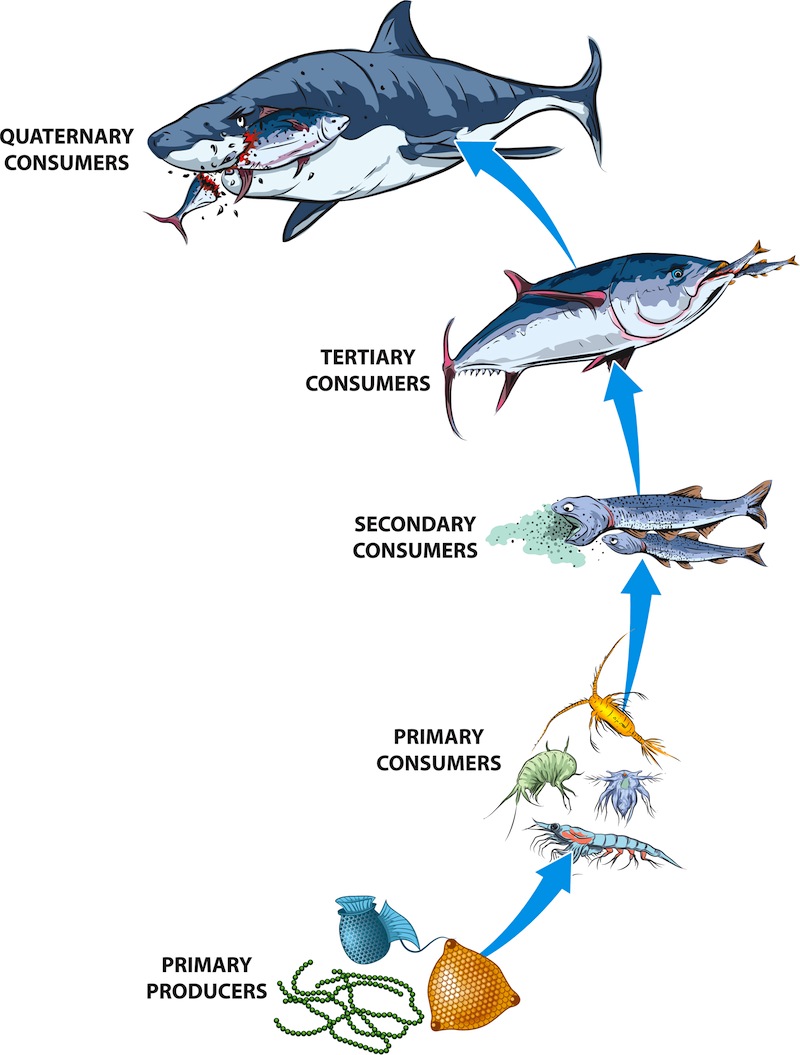

Next in the food web are the consumers. What do they consume? Producers of course! Just think of it as animals (consumers) eating plants (producers). Consumers that eat plants are primary consumers. We also know them as herbivores. Consumers that eat primary consumers are secondary consumers, better known as carnivores. And the ones with the big sharp teeth that eat secondary consumers are tertiary consumers, also known as apex predators. You might know them as lions, tigers, and sharks.

Scientists refer to the trophic level of an organism to describe where it is in the food chain. (Shutterstock)

Eventually, of course, everything dies. That’s where decomposers step in. Worms, slugs, bacteria, fungi: they all live for dead stuff, or yuckier still, the waste of other animals. For decomposers, the world is one big gooey buffet.

By breaking down dead organisms, decomposers return nutrients back into soil or water. Many decomposers prefer wet environments, so watch your step if you are exploring the rainforest. Besides recycling nutrients, decomposers that burrow, such as worms and marine worms, also churn the soil and sea bottom. That makes it easier for producers to take root and use the nutrients in the soil.

Salmon swim from the sea into the rivers where they hatched. They lay their eggs in gravel bars. Then they die. Their decaying bodies feed bears and other animals, and transfer nutrients from the ocean into the forest. (GWB / Shutterstock)

Producers, consumers, and decomposers are the biotic, or living, elements of an ecosystem. Of course, every ecosystem also needs water, air, and a physical environment. These are an ecosystem’s abiotic, or non-living, elements.

Life can’t exist without water. In lakes, rivers, and oceans, water connects and sustains all life within the ecosystem. Water carries nutrients from soil into plants and animals, and is returned to the environment by respiration and waste. Carbon and nitrogen from the atmosphere cycle through soil, plants, and animals, and back into the atmosphere. Then, it’s back to the never ending cycle. Rocks and soil influence how and where plants can grow. They also provide important shelter and nutrients.

Extreme Ecosystems

Earth’s ecosystems range from wild to mild. One of the wildest and most diverse is the Amazon rainforest of South America. Altogether, this biome and the ecosystems within it host about 40,000 plant species, 1,300 bird species, 427 mammal species, and 2.5 million types of insects. A lot of them live in the tree canopy, where sunlight reaches. Under the canopy, it’s dark. Flowers bloom big and bright. That way, insects and birds can spot them and spread the flowers’ pollen.

Far below, the rainforest floor is littered with dead organisms that have fallen from above. A lot of poop ends up there too. What a feast for the decomposers. The minute something drops in, the treasure is swarmed by eager eaters.

The Atacama Desert in Chile is at the other extreme. It is about the driest place on the planet. Some parts of the Atacama have never had any recorded rainfall. Can any organisms survive in such a severe place?

The Atacama Desert in Chile hosts one of the driest ecosystems on Earth. (Tomas Sykora / Shutterstock)

They have their ways. Near the coast, some plants get their moisture from fog that rolls in off the Pacific Ocean. Small mammals that don’t need much water scurry around at night, trying to hide from the few owls and other predators. Decomposers don’t do very well here. Some dead vegetation has been lying around for thousands of years without decaying.

But even the Atacama Desert seems friendly compared to what might be Earth’s most extreme ecosystem. Scientists drilled into a frigid lake under 2600 feet of ice in Antarctica. Imagine their surprise when they discovered a simple ecosystem there. Glaciers had ground up the rock, releasing tiny fragments of nutrients like ammonium and sulfate. Incredibly, the scientists found a microorganism living in the buried lake. It uses the nutrients from the rocks to make energy.

Return of the predators

One of our most beloved ecosystems is Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. It is famous for its wildlife. Elk, bears, deer, and coyotes all live in the Park’s vast meadows, river valleys, and forests.

Yet for many years someone was missing. It was the wolf. Wolves were once Yellowstone’s apex predator. You know: the tertiary consumer. The one with the big teeth. Some people believed other animals might be better off not being eaten by wolves. Ranchers near the park also worried that wolves might eat their cattle. So by the 1920s wolves had been hunted out of Yellowstone.

By the 1990s, the ecosystem was clearly out of balance. Huge herds of elk trampled the riverbanks and meadows. Deer had nibbled many of the aspen trees and willow plants to nubs. Riverbanks were a muddy mess. Songbirds had flown the coop, too.

In 1995 ecologists made a big, bold move. They brought wolves back to Yellowstone. They re-introduced the ecosystem’s apex predator.

Naturally, the wolves began hunting. Before long, deer changed their behavior to keep from getting eaten. They started hiding. No more munching tiny trees in broad daylight. Vegetation along streams began to recover. Some trees became five times higher in just six years. Bare riverbanks became forests again. Birds came back to those trees. With trees to hold the soil in place, stream banks didn’t erode as much. That made the rivers better fish habitat.

When wolves were re-introduced to Yellowstone, the effects cascaded down through the entire ecosystem. (Marc Schauer / Shutterstock)

Ecologists have a name for the top-down effect that wolves have had in Yellowstone. They call it a trophic cascade, for the way that changes cascade down through the ecosystem from the very top of the food chain. Some say re-introducing wolves to Yellowstone changed the way ecologists think about ecosystems. It definitely changed Yellowstone.

Back From the Dead

How do ecosystems get started in the first place? A catastrophic event in 1980 gave ecologists the rare chance to see.

On May 18, 1980 Mt. Saint Helens, a volcano in Washington, erupted violently. The eruption killed 57 people. It also destroyed every tree and animal for miles around.

Closest to the volcano, the eruption did more than just mow down living things. It buried six square miles under an avalanches of searing hot ash. The ash sizzled at 1300 degrees Fahrenheit. It covered the land 120 feet deep. Where a lush forest had been was now a lifeless, smoldering plain. No survivors.

When Mt. Saint Helens erupted, life was obliterated on a six-square mile area called the Pumice Plain. (Photo: USGS)

Could a new ecosystem take hold in this dead zone? Ecologists watched and waited. Within weeks, spiders and beetles were carried in by the wind like paratroopers. Most died in the harsh conditions. Seeds also blew in. Some seeds landed in the tiny pockets of nutrients that had been beetles. Within months, a pretty purple flower called lupine brightened the bleak landscape. Lupine has a special ability to add nitrogen to the ground. The nitrogen provided nutrients for other plants.

Gophers began tunneling under the ash. Elk took shortcuts across the grey plain. Their droppings carried more seeds from the surrounding forest. Those seeds grew, too. Slowly, small groves of brushy trees called alders began to appear. That attracted birds. A new ecosystem was up and running.

Keystone species are organisms that anchor an ecosystem. Prairie dogs are considered a keystone species for prairie ecosystems. Their burrows provide habitat for other species and help keep soil healthy. (Wollertz / Shutterstock)

Ecologists are still studying the growing ecosystem at Mt. Saint Helens. They’ve learned a lot. They’ve seen that life is tough. They’ve witnessed what can happen when animals, plants and even dead ash work together to create the amazing worlds called ecosystems.

Written by Beth Geiger

[wp-simple-survey-46]