Today I listened to the dry, papery sound of leaves skittering across a roof. Patches of yellow and red are starting appear in trees lining my daily routes. Though they are beautiful, changing leaves always evoke a feeling of loss and nostalgia. Falling leaves represent endings. In a way though, the life of a fallen leaf is just beginning—or perhaps you can think of it as a second life.

Tasks for a Living Leaf

While attached to tree, leaves perform three vital roles:

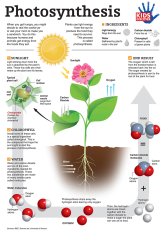

• They are the “food factory” for the tree. Photosynthesis takes place in the leaves, which provides food for the entire tree (and for its unseen fungus partners—but that’s another article!).

• They provide food for wildlife. The larvae of many insects, including moths and butterflies, feed on tree leaves.

• They provide shelter for wildlife. The most obvious might be the nest hidden away in a secret spot, but leaves also provide shelter for birds and insects during inclement weather.

Tasks for a Fallen Leaf

Fallen leaves actually perform the same three functions, providing shelter and food, though in quite different ways than when they were part of the tree.

First, layers of fallen leaves provide shelter for wildlife. Peek under a pile of leaves and you will find a cool, moist, temperature-controlled environment perfect for creatures like pill bugs, red wigglers (worms), beetles, and centipedes, plus many, many animals too small to be seen with the naked eye. This is not surprising, given that many of these animals feed on decaying organic material (which we’ll get to in more detail in a minute). However, old leaves also provide temporary shelter for overwintering animals, like bumblebees and butterfly larvae.

Second, leaf litter provides food for decomposers. When a leaf falls to the earth, the first player in the decomposition process is water. Water softens the material and leaches out sugars and other compounds. The detritivores (litter-feeding invertebrates) take over and begin breaking down the leaves further by nibbling. Detritivores include larger creatures like earthworms, millipedes, and pill bugs, smaller animals (but still visible to the naked eye—barely!) like springtails, mites, and potworms, and microbes, like protozoans. Leaf litter is also food for fungi, which are the primary decomposers of plant material. Of course, where there are plant eaters, there will also be predators, like sow bug killer spiders, centipedes, and rove beetles.

Once the decomposition process is complete, nutrients locked up in the leaves are once again available in the soil to be used by the “parent” tree. Next spring, the stage will be set for the whole cycle to start up again! In the meantime, here are a couple activities to explore the life in the leaf litter.

Activity—Leaf Pile Safari

You’ll need:

• Leaves, preferably in an undisturbed garden or park setting OR

• Leaves, one large sample per group in a gallon ziptop bag (when collecting samples for in-class use, make sure you take the sample from the bottom of the leaf layer where all the interesting creatures are residing)

• Plastic dish tubs, one for each group

• Magnifying glasses, one for each group

• Tweezers, 1-2 for each station

• Journals or record sheets for each student

• Disposable gloves for each student

• Leaf litter field guide (see resources at the end or use your own)

Instructions:

1. Set up a location/station for each group. Each station should include leaves, in a natural setting or ziptop bag, dish tub, magnifying glass, and tweezers for gentle creature handling.

2. Divide students up into groups, as appropriate for your class size.

3. Give each student a pair of gloves.

4. Assign each group (or have students choose) a location/station.

5. Invite students to investigate their sample and look for animals. Instruct them to handle creatures gently and to avoid handling centipedes. Have them note their observations with words and pictures in their journals or on their record sheets.

6. Ask students to use the leaf litter field guide or other handout to identify animals when possible.

7. Clean up, including thorough hand washing.

8. Allow students to share their findings.

Activity—Leaf Litter Food Web

You’ll need:

• Observations from the Leaf Pile Safari

• Animal identification tools (see resources at the end or use your own)

• Sample food web

• Poster board or 11 x 17 paper

• Art supplies—colored pencils, crayons, yarn, etc.

Instructions:

Using data collected during the leaf safari, have students create a food web poster. Level of instruction required will depend upon your group and how much prior knowledge they have about food webs.

Online Identification Tools

• The American Museum of Natural History has a free publication, Life in the Leaf Litter:

o http://www.amnh.org/our-research/center-for-biodiversity-conservation/publications/general-interest/life-in-the-leaf-litter

• Hope College offers an online Leaf Litter Arthropod Key:

o http://www.hope.edu/academic/biology/leaflitterarthropods/

• Cornell University has a resource called Invertebrates of the Compost Pile (leaf litter creatures and compost pile creatures are similar):

o http://compost.css.cornell.edu/invertebrates.html

Books and Websites about Food Webs

• Science for Ohio has a pdf of a compost pile food web:

o http://www.cas.miamioh.edu/scienceforohio/Composting/images/CoFoodWb.pdf

• Hungry Animals: My First Look at a Food Chain, by Pamela Hickman

• Food Chains in a Backyard Habitat, by Isaac Nadeau